ANCIENT WHALING REINVENTED. THE RISE OF AUSTRALASIAN BAY WHALING

The whole aspect of whaling in the southern seas of the Pacific Ocean was swiftly to be changed by the intervention of the colonists themselves and the adoption of a different method of whale-catching, directed against those rather sleepy Right whales (or Black whales, as they were more often called), which wandered into the little bays of Australia and New Zealand. In truth, Bay whaling was directly bound up with the settlement of Tasmania, and it was Bay whaling, too, which brought many if not most of the first non-convicts to its shores. A few years later Bay whaling brought settlement to New Zealand, and it was one of the first industries of South Australia. I shall start with Tasmania, where the adventure originated and came to be most highly developed.

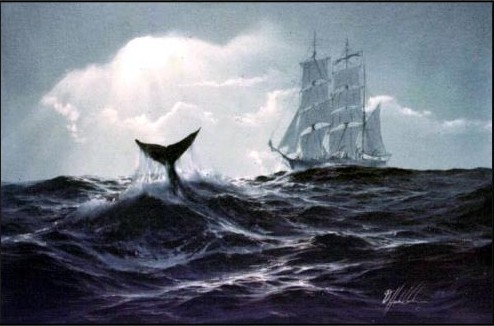

"In Search of Whales" Danny Hahlbohm |

The settlement of Tasmania was ordered by Governor King in 1803. Some say it was to relieve Sydney of the most dangerous and riotous of its convicts; others declare it was to keep the French out. A French expedition had certainly been carrying on scientific work off the coast in 1802, and this seems to have aroused Governor King's suspicions. Possibly he just tried to kill two birds with one stone.[footnote 1]

The occupation was initiated in July 1803, when Lieutenant John Bowen, of H.M.S. Glatton, was instructed to sail for the River Derwent. Twenty-four convicts, a number of free settlers and a small military force of eight men went with him. Bowen sailed to Tasmania after some trouble and delays with two ships, the Lady Nelson and the hired whaler, Albion, which famous vessel was still commanded by Ebor Bunker. Thus a well-known whale-ship took part in the very foundation of the Tasmanian colony. Indeed, it was as an active whale-ship that she took part, for Bunker, spying Sperm whales on the way, could not resist the temptation and captured no less than three of them! The expedition arrived in the River Derwent on 12 September 1803, and the new settlement on the shore was named Hobart changed to Hobart Town in 1804 (the place name only went back to Hobart without the Town in 1881).

At the beginning of the next year (1804), Bowen was replaced by Lieutenant-colonel David Collins, who arrived with a large number of convicts. It was William Collins, a naval man, who came out with Lieutenant-colonel Collins and was made the first harbour master at Hobart Town, who practically initiated Bay whaling. This event occurred almost immediately after the settlement. It could scarcely have been otherwise, for during the very first winter and spring the Derwent estuary swarmed with Right whales. They were either pregnant mothers coming close into the sheltered waters of little Australian bays all along the coast to give birth to their young, or whales of both sexes en route for the breeding-grounds.

The commercial value of this phenomenon was immediately recognized by the commanding officer, for not so long after his arrival, he wrote the following letter to Sir Joseph Banks:

|

William Collins actually drew up a plan showing how the whaling business should be carried on, using ships suitable for ocean cruising, and so combining Sperm whaling in the summer with Bay whaling for Right whales in the winter and spring. But the capture of Right whales could just as easily be undertaken from a shore station with row-boats of the usual whaling type, and this method became the common practice of the Bay whalers.

The name "Bay whaling" occurs frequently when historians deign to refer to the early Australian whaling days, and it is sometimes regarded as an invention of the Hobart men. So far as the Australian coasts are concerned that is no doubt true; but really it is the ancient method of whaling. It is supposed, for example, that the Basques fished for whales in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries along the French coast, in the Bay of Biscay; the relics of their watchtowers and boiling-pots are still to be found. The fitting out of seagoing ships carrying small whale-boats for whale capture at sea was a much later stage in the game; as also the practice of extracting the oil (trying-out) at sea. But even before 1600, French and English whalers were making voyages to Newfoundland and Spitzbergen. A little later (1613-1700), the Germans and Dutch developed a big whale-fishery at Spitzbergen, and with great success. The cooking of the blubber, however, took place on shore; and practically in all cases the whales were caught near land and were Whale-bone whales. Sometimes the blubber was brought back for oil extraction to the home country; i.e., from Spitzbergen to Hamburg or Holland. Thus the old Spitzbergen whaling of the seventeenth century may also with every right be termed Bay whaling.

The American whaling of the New Englanders originated as Bay whaling, although it never seems to have been called by that name, and even when the first vessels were sent out after Sperm whales (they were not away more than two months), the blubber was brought back to the try-works on shore.

So the Hobart men just took the natural course which Spaniards, Dutchmen, French, and Northmen had taken long years before them, wherever whales were moderately abundant near land.

An Australian Bay whaler first selected a suitably sheltered indentation of the coast, which he only leased if necessary - as when close to settled regions. Shelters were then built on shore: huts for the men, a cookhouse, cooperage, etc., and storehouses. Try-works would be built for boiling the blubber and some sort of ramp for hauling up slabs of that substance. A watch-tower or other good lookout post would he erected in a likely spot. This does not mean, however, that the whalers always waited for signals from the lookout. It was customary at many localities for the boats to pull out seaward every morning and to remain out all day or until whales appeared. If the party were a large one, there might be a steward and even a clerk attached, the latter to keep the accounts of the stores which were distributed freely at an exorbitant price to the men at the beginning of the season, so that all their possible earnings might be absorbed by the end of it.

The most important items of gear were the boats. These are worthy of some detailed description. No ordinary ship's boat that I have seen to-day is equipped with such a collection of gear as these set out with. They were clinker-built cedar craft about thirty feet long, pointed at both ends and higher out of the water at bow and stern than amidships. They varied in breadth. The stern was planked over for about five feet, and through this decking projected a short post - the loggerhead - for checking the line. Sometimes, indeed, the line was taken out so fast, and such friction resulted, that water had to be poured on the loggerhead to prevent its taking fire. A notch was often cut in this post for each whale killed.

The boats had thwarts for five, six, seven, or even eight oarsmen. The older types were five-oared boats. Those arranged for odd numbers seem to have been regarded as the best; for then, when the harpooner stood up, leaving his oar, the numbers were even on both sides. The places in a five-oar boat as it went in pursuit of the whale would be: Bow - harpooner, bow-oarsman, midship-oarsman, tub-oarsman, after-oarsman, headsman - Stern. The forrard thwart was hollowed out on the aft edge, providing a concavity or knee-brace to receive the thigh of the harpooner, so that he might be steadied at the exciting moment when both arms were extended and he needed all the support he could get whilst throwing the harpoon. At the stern the headsman, or boat-steerer, wielded a ponderous sweep which might be twenty-seven feet long, and was held in place by a leather strap. Such a device is much more efficient than a rudder when handled by one who is practised in the game. In any case, a rudder will only act when a boat is moving through the water, whilst a steering oar can be used to swing a boat's stern round at any time. When the boat was being towed by a whale the oars were "peaked," i.e., the handles were placed in sockets on the sides of the boat opposite to the thole pins, so that the oars rested almost horizontally, but with such a slope as not to catch the waves, In the typical American whale-boat there was also a mast and sail and these were by no means small, The mast-head lay under the second thwart, the mast lay over the others to project over the stern on the starboard side. So the third oar had to use his oar over the mast.

There might be one or two tubs (usually two) between the third and fourth and fifth thwarts, with 200 fathoms of line. The line was beautifully coiled in the tubs, in fact the trick of coiling properly in a tub enabled the line to be pulled out at lightning speed without getting in a mess. I can think of no other method so simple and of so little bulk which would achieve this result. The line passed right aft to the logger-head, round this, and then all the way forrard again to go through a niche in the bows, under an iron bar, and back up and over it to the harpoon. In this way, when a fast whale was performing antics, there would be no doubt of the bow of the boat being pulled foremost, a most important detail, It will be obvious that if the line were not compelled to go through some leading device at the bows it might be dragged along the side, on account of a whale's suddenly turning back, and this would bring great danger to the crew, as well as the immediate risk of capsizing the boat. I heard of one occasion when the rope did come away from the bow through the iron bar giving way. One man was immediately jerked into the sea.

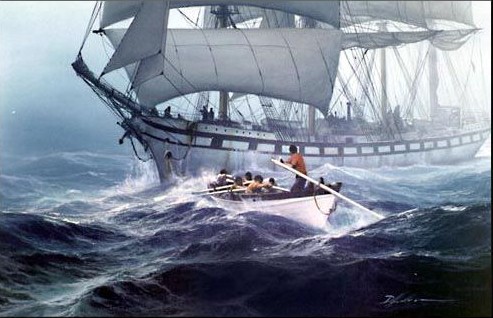

A keg of water was placed aft with a lanyard lashing it so that it wouldn't get away if the boat capsized. To the starboard side and forrard were spare lances and harpoons. A bottle of grog, coats belonging to the crew and a box of biscuits were stored away under the little deck aft, and other gear, compass, and candles or an oil lamp, wherever there was room. If you wish to know what a whale-boat looked like in close action you will see in the frontispiece what I consider to be the best picture ever made. The artist participated in such whaling.

If the Bay-whaling station were set up on the New Zealand coast the whole party might be supplied with native "wives" for the season, regular bargains being made between the headsman and the relatives of the girls. The woman was supposed to wash and mend the clothes of the man, and to cook his meals. Very frequently she kept him in order, and clean; and it is stated that these New Zealand girls often managed to obtain a surprising influence over the "wild passions of the whalemen." In any case, some sort of negotiations had to be opened up with the natives. The New Zealand Bay-whaling stations were established later than those of the Australian coast and were amongst the last to die out.

Usually a Tasmanian Bay station carried three or four boats. Since the stations were rather crowded on this coast, it often required much strategy on the part of the headsman to get his boat first to the whale. A long string of rival boats was frequently to be seen, one racing away after another - and the whale. And since the monster might at any time turn on his course, it was always possible for the first to be last, and the last first!

It is on record that as many as four whales have been taken by one row-boat in one day. But this was exceptional. The taking of twenty-four whales in a single winter by one boat was a mighty achievement, and thirty-one probably a record.

For a time the chances of making money at this new pursuit were, even for ordinary seamen, better than those encountered by an agricultural labourer in the colony, and Tasmania soon found itself short of farm hands. It must not be imagined however, that this Bay whaling was what the modern lounger calls a "cushy job." It is true that it did not involve long voyages away from land, and contact was retained with some shred of "civilization." But it was often decidedly dangerous and always rough work. Moreover, competition soon became keen (at any rate on the Tasmanian coast) ; on one occasion twenty-one boats put out after the same whale in Recherche Bay.

A whale was not killed when a harpoon of the old type entered its body. This was just the first step, the attachment or fastening which was a preliminary to lance work at close quarters. Much might happen, and considerable time elapse, before the whale was dead. It will not strain the imagination very intensely, then, to picture the quarrels that often ensued over the possession of a whale. One can surmise the brimstone quality of the language used; the Tasmanian Bay whaleman was as tough as any blue-nosed Yankee. So practically the only Australian laws appertaining to whaling until modern times were those rendered necessary in the early days to control the men engaged, and to define exactly what a "fast fish" was, and to whom it belonged.

The same need occurred when South Australian Bay whaling was started some years later. It is worth while alluding to the Tasmanian Act because few people seem to know that there were such laws. Even Herman Melville said that there were no written laws on this subject apart from a Dutch law of 1695. The Americans depended on unwritten laws!

The Tasmanian Whaling Act of July 1838, which enlarged a previous one, declared that every agreement made between owners and their employees, the whalemen, must be made in writing and signed by all concerned. A model of the schedule to be followed was given with the Act; the manuscript described in chapter 4 of this book is practically a copy of this model.

The Act goes on to say that if a whaler does not join the ship or whaling-station after signing his agreement, it shall be lawful for the police to bring him before the magistrates; and he may get hard labour for sixty days or forfeiture of his lays. If the man be a headsman he may be fined not less than £10 nor more than £100. Fines for ordinary seamen were less.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the Act is the following reference to the capture of a whale:

|

This Act concludes by setting out the machinery for protecting the rights of the employed men and their wages, and then gives permission to the Superintendent of Her Majesty's Male Orphan School in Hobart, with the authority of the Lieutenant-governor, to bind and put out to sea on merchant or whaling vessels, certain boys over thirteen years of age as apprentices.

From my own experience I find it difficult to imagine an English or Scottish fishing-village, or more particularly, the ever-dwindling fishing community of such a village, being thrown into great excitement, or roused to rapid exertion. Things were different in the days of smugglers and wreckers, and before the boarding-house era. Take, then, the contrast of the year 1820, with dawn breaking over a Tasmanian bay where two contending whaling establishments occupied relatively closely situated leases. The weather is very cold and a nasty drizzle falls at times, making visibility poor. The boats are not yet out when a sleepy lookout spies a whale and gives his cry. But at the same time the adjoining station has been similarly alarmed by its own observation post. A mad rush follows for the boats, which are launched faster than a lifeboat for a wreck; then comes the race-a race not only to circumvent the whale, but to get this done before another boat's crew can become attached and proclaim it a fast fish. The steersman, the officer in the boat, urges his men by the most blasphemous and fiery language, wielding his big steering-oar, twenty-two feet in length, with the dexterity born of long practice, and the boat tears over the waters as no sea boats are driven by oars to-day. Now they are near the whale. But it is necessary to come close, very close, indeed, and that whale may turn and run towards the rival craft Then comes the quick order from the boat-steerer-the harpooner draws in his oar and stands with his weapon poised. The throwing of the harpoon was the supreme moment of the chase. Startled by the prick of the iron, the whale would sometimes dash wildly across the water, but more often he would "sound" or sink rapidly down to the depths.

It is impossible to throw a harpoon very far. Try and picture it, those of you who know the sea and the ways of small boats. The Humpback whale is the mildest of creatures, the Right whale heavy with her unborn child could not possibly be regarded as a ferocious monster, but in either case it needed but an unexpected flick of the tail, as leviathan (whether alarmed, or irritated by the harpoon prick) dived for safer regions, to smash the whalemen's craft to splinters and to throw the crew headlong with the serious risk of being entangled in the rocket-like whirl of good Manila rope. Most frequently a harpooned whale threw his posterior half out of the water in a windward direction. It was desirable, therefore, to approach head-on and slightly on the lee side. But a stove boat was quite a frequent occurrence, whatever was done.

That interesting character, Oswald Brierly, [footnote 2] set down a brief account of one such experience in early Australian Bay whaling:

|

"Rescue" Danny Hahlbohm |

Many a whaler has been carried to his death below the waves in a noose of the line; sometimes a leg would be caught, sometimes the neck, and the unfortunate seaman strangled as he was drawn down.

The whale having been struck, the harpooner's duty changed-he took the steersman's place. After a varying interval depending on how long his breath lasted, the whale would come up to the surface and then swim with all his might-and it was some swimming-dragging the boat after him. Probably this was the first approximation to speed-boat racing the world ever saw. It was called a "Nantucket sleigh-ride." And during it the line would be hauled in or let out as might be necessary. The officer would now be ready at the bows with the lance. To him belonged the task of killing the whale, but hours of arduous work and danger might elapse before the whale was dead.

"The greatest peril came when the whale raised his `red flag,' so to speak, when he spouted forth a spray of blood from his spiracle." Then it was that he would go into his "death flurry" (see frontispiece), dashing madly about, before rolling over, dead. And then it had to be towed to the beach; an impossible task if the whale became water-logged and sank to the bottom. This sinking through lack of buoyancy sometimes happened with the species of whale pursued by the Bay whalers. It was almost a certainty with other sorts; and it was this certitude (with other causes) which preserved certain species from capture on the high seas in those days. When sinking occurred in shallow waters completion of the work would have to wait until the distension of the whale by the gases of putrefaction brought the carcass to the surface again. Then the removal of blubber was a stinking as well as a bloody business.

The sinking of a whale in deep water was also another source of danger in addition to the certain loss of harpoons, lances, and rope. Taking everything into consideration, the Bay whalers deemed it more easy to kill a whale than to get it to the shore. They cursed at the back-breaking work of the everlasting rowing.[footnote 3]

Those hosts of whales which invaded the Australian coasts in winter-time were, as pointed out above, pregnant mothers, or else mating whales. We know now that they came from the Antarctic after the close of the cold southern summer, leaving their rich feeding-waters near the ice for the more salubrious seas where they carried on their love-making and gave birth to their young. Springtime brought a return to the icy regions. They suspected no danger of a human sort on these migration routes, which had probably been established and sustained undisturbed through countless centuries and numberless whale generations.

William Collins, the originator of Australian Bay whaling, had probably the first station, which was established in 1806 at Ralph Bay on the east side of the Derwent. The killing of the first whale in the Derwent is claimed by a curious character, Jorgensen, [footnote 4] about 1804; it is definitely stated by the Rev. R. Knopwood in his diary, however, that whales were killed opposite his camp in 1804 by men from a whale-ship. So if Jorgensen were the first it was a matter of days. Other stations were soon established at Tinder Box Bay, and Trumpeter and Adventure Bays, and very many others grew up quickly in the years that followed.

It must not be supposed that the new Australian methods of whale capture replaced the whaling from the "blue water" whale-ships of America and Europe, which in ever greater numbers entered the southern Pacific. Sperm oil was more valuable than Right whale oil. In any case, whalers who came from far countries found that the Bay-whaling season was a short one and could be made to fit in with their Sperm whaling. The River Derwent country appealed to the whalers very much. I am not surprised at it. It is a beautiful spot to-day, and in those bygone times it had all the advantages the whalemen could wish: timber for masts and spars, fertile lands for the production of food-supplies, and at times, hosts of whales. Sometimes fifty to sixty of these cetaceans might be seen between May and November in the shallow parts of the river itself! Day after day, in 1804, Knopwood in his diary refers to whales in the river. Here is one such entry:

|

It is said that on one occasion the snorting of the whales at night actually kept the Lieutenant-governor awake! Needless to say, such sights have long since passed into the limbo of things forgotten-and, although perhaps it is a rash statement for a scientist to make, they will never be seen again. The Right whale is now a protected animal under the whaling laws of the great whaling nations. It is a rarity of the seas where it once abounded, and was ruthlessly slaughtered.

Bay whaling spread rapidly from Tasmania over a wide range of the South Australian coast, and ocean-going whale-ships from America, Great Britain, France, and Sydney set up shore stations and made temporary land bases in safe inlets everywhere. And so there is ample truth in the little-known statement of Melville quoted in the introduction.

The era of Bay whaling extended from 1805 to, say, about 1845. In 1841 there were thirty-five Bay-whaling stations in Tasmania alone.

The rise of Hobart might almost be ascribed to its business in Bay whaling; for those engaged in it naturally turned to Sperm whaling in the days after 1840, when the Right whale ceased to come to the slaughter. Then Sperm whaling encouraged local shipbuilding. Hobart has never lost its reputation for wooden ships. A Hobart-built yacht is a very desirable craft in these shoddy days.

There would be little point in attempting to tell of even a few of the Bay-whaling stations of Tasmania. There is material enough for many novels in the odd descriptions left us, but whilst the human element varied as life does vary, there was remarkable uniformity in the conduct of the enterprises. References appear now and then in the simple newspapers of that day. I cannot help quoting one from the Hobart Town Gazette of 29 June 1816, just as it is printed, for it ran with scarcely any break into an amusing matrimonial notice:

|

Verily the papers of those days are not without amusement for the searcher of to-day. And look you at the interest of the first simple announcement. Evidently the arrival of the Right whales at the end of June was an event of almost clock-like regularity in those days of cetacean plenty.

The early newspapers might have given us more thrilling local news had not news from England always taken first place in the minds of the Australian pioneers. On one occasion, amidst short announcements on whaling and shipping, escaped convicts and drunken sailors, thieves and hop-growing, there appeared a letter from London, rather droll to us of to-day, but telling of something startling and wonderful then. Did any one guess that it was a zephyr from an awakening world beyond the seas, where science was about to destroy many of the old uses of whale-oil before it created new needs for it, and new methods of satisfying them?

|

Well, well, and to think that some artistic folk of to-day prefer oil lamps even before the electric light! How tongues must have wagged over the rum and beer in the Ship Inn and the Union Tavern when such news arrived from the "Old Country."